In a

recent

CFR article, Ed Husain argued that Syria’s ongoing civil war is

overshadowing the infiltration of Al Qaeda into the rebel forces, and they are now

winning the ideological battle for the revolution. Although acknowledged by

western policymakers including CIA Director Leon Panetta, the presence of the

terrorist group has not stopped leaders such as French President Francois

Hollande from declaring that they would recognize any interim government formed

by the Syrian government. Such a move would completely disregard the fact that

no interim government could be formed without the support of the

well-organized, amply funded and armed Syrian Al Qaeda.

As

early as May, Panetta admitted that the U.S. believes that Al Qaeda has

established a solid presence in Syria among the ranks of the Free Syrian Army, or FSA, but that the nature of their movements

and organization were still cloaked in mystery. The group believed to be behind

the Al Qaeda attacks of recent months calls itself Jabhat al-Nusra l’al-Ahl

al-Sham, or Victory Front of the Syrian People. Al-Sham is the traditional name

for the region encompassing Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Jordan and Israel, a

reference to the group’s long-term goal of redrawing the regional borders

starting with a liberated Syria.

An FSA fighter on the streets of Homs. Photo by Bo Yaser.

The

term “liberation” is, of course, misleading when it comes to Al Qaeda. What

“liberation” means to them is a casting off of both Asad and Western influence,

to be replaced with a strict form of Sunni Islamic law, a totalitarian

religious government, and a continuation of jihad waged against countries like

Israel. Jabhat al-Nusra benefits from many of the same circumstances that

allowed Al Qaeda to gain a foothold in Afghanistan in the 1980s: a welcoming

population, ideological appeal, a steady supply of weapons and money from Arab

donors, a pre-existing conflict in need of recruits, and Western reluctance to

interfere. Much like the Taliban discovered their regime could not succeed

without the Al Qaeda mujahideen, any interim government will find itself unable

to dislodge the extremist elements within the opposition once they have become

a crucial part of its operations.

According

to Husain, the group had already conducted 66 attacks in Syria by June,

including many car bombings that the Asad regime was quick to publicize for the

international community as terrorist attacks. The global community for its part

is even less likely to give aid to a Syrian opposition it views as infiltrated

by extremist Salafi jihadists. Overlapping political affiliations in Syria already

make any direct support of the opposition complicated at the very least; that

the likely outcome of such aid would see U.S. weapons in the hands of a group

like Al Qaeda precludes such support from becoming reality. After all, America

learned its lesson the hard way in Afghanistan when the mujahideen it had armed

against the Soviets became the terrorist group responsible for 9/11 and some of

the most fervently anti-American organizations on the planet. Many of the

Syrian jihadists are thought to be from Anbar Province in Iraq, and as such

they are not an unfamiliar enemy to the United States.

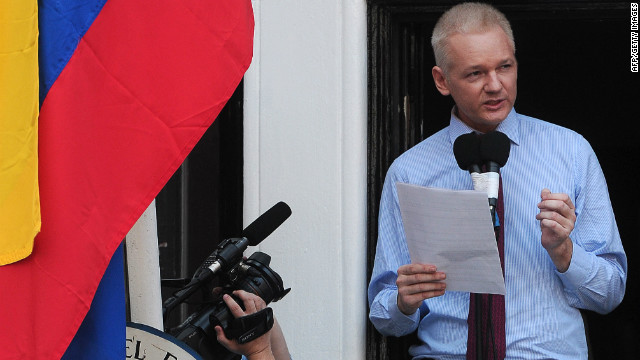

The

Syrian opposition itself is fully aware of how precarious its position is,

especially given that it will eventually need outside support to survive. It

has deliberately tried to hide the Al Qaeda-associated groups within its ranks

from the view of the media. When reporters discovered opposition soldiers

sporting Al Qaeda’s flag in a neighborhood in Damascus, they were ushered away

by opposition leaders before they could interview the fighters. The Free Syrian

Army has rejected videos and photos blatantly showing opposition soldiers

wearing Al Qaeda symbols and insignia.

Syrian opposition fighters stand behind an Al Qaeda flag.

Yet

the evidence is mounting that without Al Qaeda, the resistance would be nowhere

near as successful as it has been. Which

means that Jabhat al-Nusra has the power and the resources to demand a part in

whatever government emerges from the Syria conflict. While Western countries

have wasted no time disavowing Asad, they have been much slower to provide

concrete support to the opposition forces that desperately need it. In part,

the opposition can thank groups like Jabhat al-Nusra both for propping up the

rebellion, and also, perhaps, condemning it.