Today marks a somber anniversary, the 70th

anniversary since the United States dropped the first of two nuclear weapons on

Japan. Seven decades ago today, the US, ostensibly

to end WWII in the Pacific, dropped a nuclear bomb on Hiroshima, followed three

days later by a nuclear attack on Nagasaki. In the aftermath, hundreds

of thousands of people died in the two cities, and over one hundred thousand

were killed in the initial blasts alone. The nuclear weapons used in the

attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were comparatively small compared to the

destructive power of nuclear weapons today, and they still devastated two large

cities. Japan marked the occasion with speeches by the few remaining survivors,

a national moment of silence, and the tolling of a bell.

| Pres. Obama speaks on the nuclear deal at American University |

The anniversary comes at a moment when the United States faces yet another nuclear crossroads: whether or not to enact a nuclear deal reached with

Iranian negotiators on July 14. On one side stands the Obama administration,

which negotiated the deal and hopes to pass it through a Congressional vote, despite

significant, somewhat bipartisan opposition. On the other stand politicians

from both sides of the aisle, although largely Republican, who say the deal

will not stop Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon, and argue that the US

should continue the current sanctions regime in the hopes of obtaining a better

deal. If such a deal never materializes, then armed intervention in Iran

becomes an option.

Pres. Obama faces large hurdles of domestic opposition to

ratify the deal. His current speaking tour, which includes domestic audiences

as well as meetings with Israeli groups, is aimed at explaining the deal’s

merits to those who would oppose it, largely on the grounds that it doesn’t go

far enough to ensure that Iran does not build a nuclear weapon. At American

University yesterday, the President argued

that “The choice we face is ultimately between diplomacy and some sort of war —

maybe not tomorrow, maybe not three months from now, but soon…How can we in

good conscience justify war before we’ve tested a diplomatic agreement that achieves

our objectives?”

Iranian Pres. Hassan Rouhani also faces substantial domestic

opposition, largely from the conservative hardliners in his own government and

their constituents. To generalize, this group includes much of the powerful

clerical establishment and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, many of whom

profit from the black market created in the wake of international sanctions,

and thus want the regime to continue. This same group was able to sweep Mahmoud

Ahmadinejad to power after a period of greater progressivism in the early 2000s,

after Pres. Mohammed Khatami’s attempts to make overtures to the Bush

administration, especially after 9/11, fell flat. If Pres. Rouhani doesn’t

deliver on his promise that the deal will allow Iran to end its economic

stagnation and create opportunities for its growing population of (mostly

educated) young people, he runs the same risk as Khatami: namely, a return to a

conservative stranglehold over Iranian politics.

Concerns over the Iranian nuclear deal today are not without

precedent. Both Presidents John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan negotiated nuclear

arms deals with the Soviet Union, despite that country’s direct and imminent

threat to America, and they faced significant – and similar – domestic

opposition to the deals they struck. Many detractors of the Iranian deal are

primarily concerned with the threat Iran poses to Israel, a country with which

it has had existential conflicts since the Islamic Revolution in 1979. In

defense of one of the US’s closest allies, it is only natural that Israeli

citizens feel the same concern that American citizens did on the eve of the

US-Soviet arms agreements: nuclear treaties – any treaty – are inherently

uncertain, largely constructed around verification systems that could possibly

fail. But Israelis and US citizens alike should look to history to see that these arms deals worked, despite the

larger threat the Soviet Union posed to America and its allies by virtue of its

existing nuclear stockpile. The deals not only made Americans safer, but they

also made the entire world safer, to the tune of nearly 70,000 nuclear

weapons. At the Cold War’s height in 1986, there were an estimated 86,000

nuclear weapons stockpiled worldwide; today, there are only 17,000, 90 percent

of which are owned by the US and Russia.

|

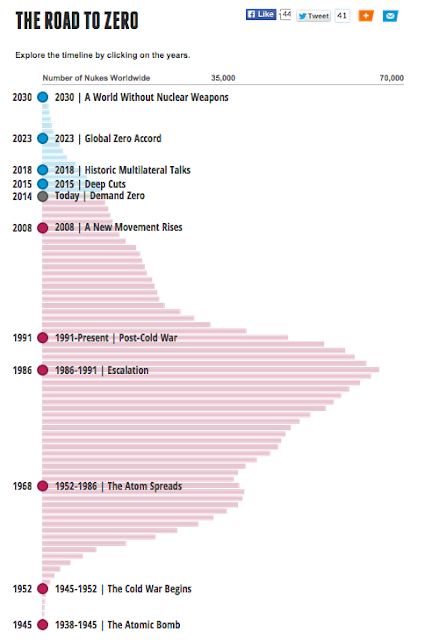

| "The Road to Zero" nuclear weapons since their invention, courtesy Global Zero |

Did arms deals mean that America and the Soviet Union became

buddies, or even close allies? Absolutely not, and it’s not likely that Iran

and Israel will enjoy a friendly relationship in the near future. Yet, in the

long-term, an Iran that is more closely tied to, and thus more dependent upon,

the international community is an Iran that is constrained in its options to

antagonize or attack Israel. An isolated Iran is a more dangerous Iran, and

without a nuclear weapons deal, it will continue on its path to the bomb

regardless, with far fewer mechanisms in place to stop it before it is able to

build a nuclear weapon. Many nuclear experts have lauded the terms of the deals, while others have expressed concerns over the verification mechanisms of the deal. While verification

methods are certainly not foolproof, even less certain is the future of the

Iranian nuclear program absent such a deal, and absent any verification

mechanisms at all.

Of course, security fears are only one part of the

opposition puzzle. As I have written previously,

US allies in Riyadh and Tel Aviv are also making economic calculations, while using security as a pretext to oppose the deal

publicly. In reality, many policymakers in these two countries are more fearful

of the implications of an economically integrated Iran than the (now lowered) risk that Iran obtains a bomb despite the deal, understanding that it

will emerge from sanctions as one of the best-educated and largest populations

in the region. A bigger slice of the economic pie for Iran does not necessarily

need to mean less for everyone else, but it does mean that Saudi Arabia and Israel

will be more constrained in their choices, both economically and

politically. But what such fears ignore is that it also could mean a stronger

regional economy as a whole, and one where two oft-opposing powers find common

ground and, perhaps, a greater sense of cooperation.

If the domestic debate surrounding

the nuclear deal with Iran could be boiled down to simple opposing choices (and

it can’t, but it’s a useful exercise nonetheless), it will be the choice

between two visions of American foreign policy: for supporters of the deal, the

way forward is one not of belligerence and unilateralism, but of diplomacy;

sanctions and international cooperation have achieved their stated goals of

bringing Iran to the negotiating table, and the way forward now can only be

achieved through similar cooperation and negotiation.

For the deal’s detractors, especially among conservative US

politicians, America’s foreign policy should continue forward on the path set

out by George Bush in 2003: rather than rely on the international community to

verify Saddam Hussein’s alleged nuclear stockpile, America acted unilaterally

in a failed quest to find weapons of mass destruction to justify invasion after the fact, which resulted in the ongoing

war in Iraq that has destabilized the entire region.

The cost of US policy in Iraq? The lives of nearly 5,000

American soldiers, more than half a million Iraqis, and the rise of ISIS.

A war with Iran, whose government is more stable, military is better armed, and

whose nuclear program is far more advanced than it would be under the terms of

the deal, would be even more catastrophic for not only the United States, but

also its allies in Israel and Saudi Arabia. The choice before the US Congress in

September will be whether or not we, the American people, would be willing to

bear that cost, or if we should at least try diplomacy, before resorting to

war.

No comments:

Post a Comment