Just under a year ago, when the number of

Syrian refugees had just topped a million people, the conflict had already

caused the largest refugee diaspora and humanitarian disaster of the decade.

Over the last year, the crisis has grown exponentially, and there are now more

than 2.3 million registered refugees according to the UNHCR. There could be as

many as three million when unregistered refugees are taken into account. In

2013, more than 1.7 million refugees were registered by the UNHCR, 3.4 times

the amount that registered the year before. The UNHCR has thus requested $4.2

billion in additional funding to assist it and more than 100 other agencies as

they deliver life-saving aid to refugees both in camps and out, as well as to

their host communities.

The UN’s Regional Response Plan (or RRP), now

in its sixth revision, focuses on responding to two key areas of aid delivery:

essential needs and services, and protection. Essential needs and services

range from food security, shelter, health and nutrition, education, water,

sanitation and hygiene, and livelihoods. Of particular concern are the 30% of

refugee children not vaccinated against measles and polio, leading to the

resurgence of polio within Syria, and fears of an outbreak in the region. Additionally,

most of if not all of the refugees have experienced trauma of some kind, and

psychosocial health care must be provided if they are ever to recover. The UN highlights

education as a key concern, amid fears that the Syrian refugee children will

become a “Lost Generation” after having witnessed horrific acts and spending

years out of the classroom. Basic

access to shelter has been an issue in every host country, and 420,000 refugees

in the region live in “tented, non-permanent accommodations,” while 105,000 live

in “substandard informal settlements.”

Protection aid covers issues such as Sexual

and Gender Based Violence (or SGBV), the protection of children, providing

documentation and preventing statelessness, and seeking durable solutions for

refugees in temporary accommodations.

Each of the receiving countries in the region

that is taking in significant amounts of refugees experiences burdens on their

infrastructure in differing ways. While all of the above issue areas are

present in every country, they occur with varying degrees of severity, thus

offering priority areas on which humanitarian groups can focus their efforts.

Every country has also experienced strains between the host communities and the

refugee populations, leading the UN to include 2.7 million vulnerable members

of host communities in the RRP 6.

This is one of the largest humanitarian

disasters since the Rwandan Genocide, which will demand a corresponding amount

of energy to resolve. For instance, less than 40 percent of refugee children

are currently in school. If the Syrian refugees were a country, they would have

the lowest school enrolment rates in the world. Over the next year, over 4

million people in the region, both refugees and host country citizens, will

require water assistance. Polio, the measles, and other diseases could return with

a vengeance to a region once rid of them. Syria itself has lost an estimated 35

years of human development, and if the refugees are left uncared for, there is

no telling what a post-conflict Syria would look like when they begin to

return.

The toll of human suffering and regional

instability will become insurmountable if the international community does not at

minimum step in to fund the relief efforts of the UNHCR and other agencies. Doing

so will provide a basic foundation from which to begin rebuilding after the

conflict ends. Following the international donors conference in Kuwait on

January 15, only $2.4 billion of the $6.5 billion requested by the UN, both for

the refugees and for those in need within Syria, was pledged. With only 60% of

pledged funds actually delivered last year, it is unlikely at this point that

aid agencies will be able to do more than place Band-Aids over the gaping holes

in available resources, to the long-term detriment of the region and the

international community at large.

The contiguous states of Iraq, Turkey,

Lebanon, and Jordan have absorbed the brunt of the Syrian refugee crisis,

although it is worth noting that Egypt is now host to over 130,000 refugees.

More than four million refugees are expected to flee Syria by 2015, of which

84% will live outside of camps, presenting further obstacles to aid delivery

and exacerbating strains with host communities.

|

| Peshkhabour crossing, where 40,000 crossed in one week. |

60 percent of the refugees live in non-camp

settings, while 40 percent are within camps, where services are markedly better,

but by no means outstanding. Within Domiz, the largest established camp,

overcrowding has led to inadequate Water, Sanitation and Hygiene access, and as

a result waterborne illnesses such as diarrhea tripled in the last year. Outside

of the camps, even in established “transit areas,” there is severe overcrowding

and even fewer resources.

The education of Syrian refugee children is

in crisis in Iraq. Only 5-10% of children are in school, owing to language

barriers, lack of classroom spaces, and the need for children to earn a wage. Planned

interventions for 2014 focus on providing classrooms closer to refugee

settlements in and out of camps, providing catch up classes for students who

have been out of school for one semester or more, and training teachers in

Arabic instruction.

Ongoing political instability in Anbar

province, where one of the 13 refugee camps and transit areas in Iraq is

located, has created confusion between Syrian refugees and those fleeing the

fighting in Ramadi and Fallujah. Because of the unstable situation,

approximately 20,000 refugees returned to Syria last year, primarily to the

Kurdish areas. Others cross the border into Iraq to collect supplies and return

to Syria, despite the danger from mines along the Iraqi border. As inhospitable

as Syria has become in the course of its three-year civil war, in some areas,

it is preferable to the unstable environment in Iraq.

Turkey has been one of the most responsive

host countries to the refugee crisis, benefiting from a relatively large

population and territory as well as greater resources. More than 570,000

refugees now reside in Turkey, with 36 percent living in camps and 64 percent

in urban areas. Up to a million refugees are predicted by the end of 2014, due

to increased fighting between rebel groups in northern Syria. Relief projects

have shifted focus from camps to urban settings, where many of the newest

refugees are settling. Syrians have been given cash grants to start businesses

as well as cash assistance on bankcards. Within the camps, school enrolment is

at 60 percent, while outside it is just 14 percent, primarily due to language

barriers and the need for child labor to sustain families.

|

| Tents with the Turkish government's, not UN's, insignia |

Lebanon and Jordan have experienced the most

acute drain on their infrastructures and capacity to provide aid due to the

large proportion of refugees to their native populations. Lebanon, already home

to approximately 260,000 Palestinian refugees in a population of over 4.4

million, now hosts 890,000 registered Syrian refugees with 1.5 million

projected by 2015. That doesn’t include the 100,000 Palestinian refugees

fleeing from Syria into Lebanon by 2015, as well as 50,000 Lebanese returnees

predicted to reenter the country this year. The UNHCR estimates that 1.5

million Lebanese will need assistance to cope with the influx in 2014. Overall,

refugees now make up at least a quarter of the population of Lebanon, with some

estimates placing the proportion closer to a third of the population. To put

that in perspective, in the United States, that would be as if one hundred

million refugees poured over the borders in just three years.

Because the pre-conflict economic links

between Syria and Lebanon were so strong, one of the greatest costs to Lebanon

has been to its economy: the World Bank estimates that GDP growth rates have

decreased by 2.9% every year of the conflict, at a cost to the economy of $7.5

billion by 2015. Also according to the World Bank, $1.4-1.6 billion are needed

to simply restore public services to pre-conflict levels, services that were

already inadequate to meet the needs of the native population. As a result, UN

programs have focused on aiding areas with high numbers of both refugees and

poor Lebanese to try to double the effectiveness of programs. Aid agencies attempt

to “buy Lebanese” to bolster local economies and offset some of the costs of

the conflict.

|

| A shelter made of 'Hunger Games' posters in Lebanon. |

The Syrian refugees in Lebanon are also

experiencing difficulty acquiring adequate water and food. 27% of refugees do

not have access to potable water, and 80% cannot provide food for themselves. Rising

prices for food, water, and housing negatively affect local populations as well,

and aid efforts aim to provide assistance for these groups if given adequate

funding. Additionally, overcrowding and poor sanitation heightens the World

Health Organization’s concerns that waterborne diseases and measles or

tuberculosis, could break out at any time.

The lack of resources has heightened tensions

with the locals that have often spilled over into violence and exacerbated

Lebanon’s political standoff between sectarian parties. High profile

assassinations and the resignation of the government have served to make things

worse, and Lebanese attitudes from every religious sect and region have begun

to turn against the refugees. A commonly cited statistic is that 170,000

Lebanese will be pushed into poverty this year due to the downturn in the

economy, and there have been calls for closing the borders from every corner. Palestinian

refugees from Syria are already barred from entering the country, although at

most checkpoints they can reportedly pay an extra bribe or fee for entrance.

Finally, Jordan is quickly coming to the

limits of its capacity to serve both refugees and vulnerable host communities,

largely owing to the portion of its population now made up of these groups. Unlike

Lebanon, Jordan does have four completed refugee camps and one under

construction at Azraq. The largest refugee camp, Zaatari, is now the fourth

largest city in Jordan. Still, 80 percent of refugees live outside of the camps.

With 592,000 refugees in the country, they make up about 10 percent of the

total population, and the refugee population is expected to grow to 800,000 by

2015. One positive development in Jordan is that aid agencies have caught up on

the backlog of unregistered refugees, allowing them to better estimate for and

provide services to both the refugees and the host communities.

Education is another area where the Jordanian

government and aid agencies have made some progress. Thanks to a successful

“Back to School” program that included “double-shifting” Jordanian schools so

that Syrian children could attend special courses in the afternoon, 55% of

Syrian refugee children are now in school. This is especially important in

Jordan because the majority of refugee children come from rural areas with

lower levels of education to begin with. Major barriers for refugee children

still exist, however, as Jordanian schools begin instruction in English earlier

and children are required to have a UNHCR registration card to enroll.

The issue areas in Jordan that are of major

concern to aid agencies include SGBV, unemployment, and access to food and

water. SGBV in particular is widely reported among Syrian refugees in Jordan,

and 40% of women and girls report staying inside most or all of the time due to

security concerns and harassment. In the camps, many report feeling unsafe in

Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene facilities, especially due to the lack of

adequate lighting and security. Negative coping mechanisms such as early and

forced marriage, prostitution, and survival sex are also common, and further

monitoring and prevention funds have been requested by aid agencies.

One of the reasons negative coping mechanisms

are so prevalent has been widespread unemployment. Unemployment is extremely

high among the refugees, as 90% of working-age refugees are unemployed, the

highest rate in the region. Agencies have emphasized the need for education or

training programs to divert young men from illegal or violent activities due to

a lack of employment. Within the camps, informal economies have replaced formal

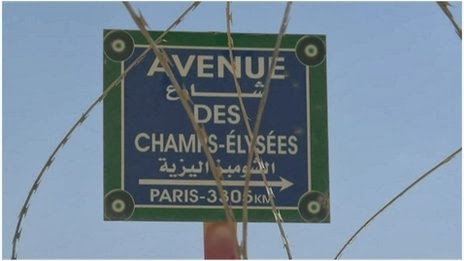

employment, and in Zaatari the main thoroughfare, where one can find everything

from bridal gowns to kebab shops, has been renamed “Avenue des Champs Elysees” after the famous Parisian street. The abundant bridal

shops along the street point to another disturbing trend: women using marriage

as a defensive tool, hoping a male protector will be able to shield them from

SGBV and harassment.

|

| Main street in Zaatari refugee camp. |

Yet another common thread between Jordan and

Lebanon, other than the high ratio of refugees to the local population, has

been tensions with the host communities. Jordanian communities in the north in

particular are impoverished and were formerly aid recipients themselves, only

to be sidelined now by aid designated for refugees only. A key part of the RRP

6 for Jordan is assisting both impoverished host communities and refugees, but

without ample funding most of the resources will be concentrated on the latter,

raising the risk of conflict and border closures. Like Lebanon, the borders

have already been closed to Palestinian refugees trying to flee Syria.

While funding alone will not end the Syrian

conflict nor return refugees to their homes, it will provide a desperately

needed lifeline of support for both refugees and their host communities. As

former US ambassador to Morocco Edward M. Gabriel remarked at a recent meeting

on the crisis at the Woodrow Wilson Center, the failure to adequately share

this burden and assist the refugees and host communities would be a

“prescription for future hopelessness and attraction to radical ideologies.” The

greater Middle East was already the host to the largest population of refugees

in the world prior to the conflict, and the tremendous generosity and

hospitality of the host governments reflects their preparedness to help. This

preparedness, however, is being tested by weak economies and infrastructures,

and without the aid of the international community, there is no guarantee that

borders will remain open, or that contiguous states will remain peaceful.

Great piece, Vicky! I was wondering about the pattern of underfunding UN requests - why is this? Are the member countries distrustful of UN money estimates or are they just being wienies?

ReplyDelete