The World Health

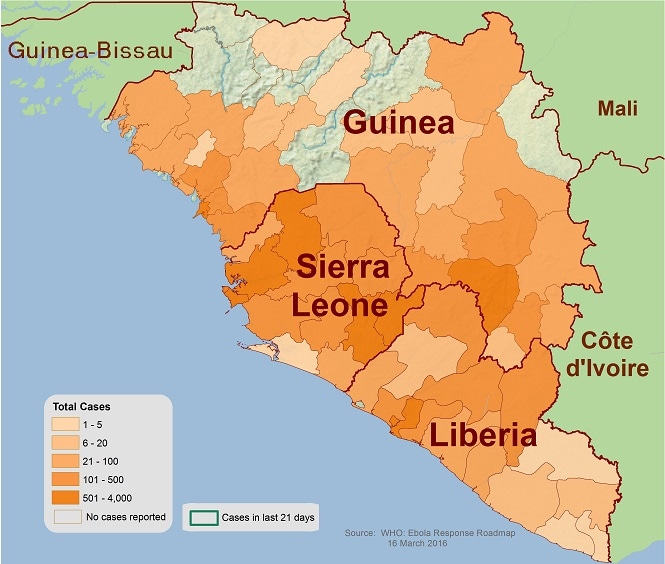

Organization (WHO) was notified of the first cases of Ebola in Guinea, West

Africa in March 2014. Since then, the virus has spread past Guinea, thanks to

the region’s porous borders, into Sierra Leone, Liberia, Senegal, and Nigeria.

With a fatality rate of 70%, slightly lower than the 90% fatality rate of past

outbreaks, Ebola has had a chance, due to unprepared public health systems and

poorly informed citizenry, to spread steadily through the region. Ebola is

thought to have spread to humans through fruit bats, which are considered a

delicacy for some West Africans, as well as through other types of bush meat such

as small rodents.

While Ebola does not

spread quite as quickly as the Spanish flu or pre-vaccination days measles,

efforts to contain the disease have already exceeded the capacity of public

health systems in West Africa. The total case count of the disease has reached

6,574, as of September 29th, according to the US Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention (CDC). According

to the CDC, the total number of laboratory confirmed cases is 3,626 and the

total number of deaths is 3,091. The overwhelming majority of these cases have

been documented in Liberia (3,458 total cases, 914 laboratory confirmed cases,

and 1,830 deaths), with Sierra Leone running a close second (2,021 total cases,

1,816 laboratory confirmed cases, and 605 deaths). In Senegal, no new cases

have been reported since August 29, and in Nigeria, no new cases have been

reported since September 5. In Guinea, the infection rate seems to have

stabilized.

How many people are or will be affected?

Gaining an

accurate total of the number of Ebola cases has been complicated by several factors, the first being simply that

many cases of Ebola are going unreported. The CDC estimates that for each

reported case of Ebola, another 1.5 cases are not documented. Part of this is

caused by understaffed clinics and hospitals that lack the resources to admit

and treat everyone who shows up, leading to an incomplete total count of

afflicted persons. A failure to self-report further compounds the problem. In

many communities, there is a stigma attached to Ebola, and people are unwilling

to admit that someone in their family or household is showing symptoms of or

has Ebola. The threat of quarantine or restrictions on freedom of movement also

make it less likely that people will self-report, further hindering efforts to

stamp out the disease.

Creating a

predictive model to project the potential impacts of Ebola before the epidemic

ends has also proven difficult. The CDC is working with data being reported

from disconnected streams, which increases the possibility for duplicate

reports of the same cases. Differences in reporting reliability and variations

in levels of underreporting make it difficult to apply accurately one

predictive model across all of West Africa.

The efforts to

combat and contain the spread of Ebola have been hampered not only by a lack of

resources available to the local governments and medical centers, but also by

the general distrust that Western medical response teams have encountered.

Rumors that Ebola is a conspiracy by the Americans or the Western world to kill

the locals have led to tense relationships between local communities and aid

workers, escalating in one publicized instance to the incident in Guinea this

past month in which the members of a health delegation were actively targeted

and killed by the local community. Such beliefs also dampen the likelihood that

people will seek professional medical attention or follow proper sanitation

protocols if and when they begin to show symptoms, thus increasing the risk to

their family members, close friends, and untold others.

Local Efforts and Challenges

In Liberia, Médecins

Sans Frontières (MSF) is attempting to double current capacity to 400 beds at

its facility in the capital city of Monrovia by the end of the month. To ensure

adequate treatment, the facility is increasing staff as well. MSF’s Monrovia facility

currently has 617 health care workers for the 200 beds. However, death toll for

Ebola victims is rising rapidly in Liberia mostly due to the lack of access to

medical care. Most infected people are treated in their homes by family members

who then contract the disease. Even when ambulances and response teams make it

to the countryside, they do not have the capacity to transport all of the

infected people back to a hospital or mobile clinic. They also face resistance

from people who are afraid to leave their families to go, very likely, to their

deaths in a cold hospital room surrounded by foreign health workers covered

head-to-toe in protective gear. The country does not have the resources to

force infected or potentially infected persons into treatment in isolation

units in hospitals.

In Sierra Leone,

where about 600 people have died of Ebola, a quarantine and curfew have been

imposed on five of the 13 counties, affecting mobility for a third of the

country’s 6 million citizens. Quarantine has led to riots and frustration as

people are disappointed with the lack of progress in ridding the country of

this disease. Further frustrating efforts to combat the spread of the disease,

funeral customs and traditions in the region run counter to the safe burial and

disposal protocols necessary to prevent infection.

US Efforts

Local

governments in West Africa unfortunately lack the capacity to combat this

epidemic on their own. The US has taken the lead in a four-pronged effort, with

the support of the international community. The strategy commits the expertise

of the US military to coordinate and facilitate international relief efforts by

expediting the transportation of supplies, medical equipment and personnel, to

build Ebola Treatment Units in hard hit areas, to set up facilities to train an

additional 500 medical staff per week. USAID, along with other US Government

agencies, is spearheading efforts to disseminate awareness and protection kits

primarily in Liberia, as well as across the region. Complete details on the US

strategy can be found here.

The Pentagon

announced yesterday that it would be bolstering its existing efforts to combat

Ebola in West Africa by deploying the 101st Airborne

Division. The 1,600 US troops will be assisting in coordinating the global

response to the Ebola epidemic. In addition to these troops who will be trained

on the particulars of the disease and personal protective equipment, there is

also a team of 700 engineering troops en route to the region tasked with the

building treatment centers desperately needed to treat infected people. These

engineers will be joining the US Navy’s construction arm, which began assisting

crews in Monrovia, Liberia last week in the development of treatment and

training centers.

International Efforts

With infection

numbers surpassing 6,500 by the end of last month, and reported numbers

estimated to be about half or ⅓ of total infections, the international

community has been quick to make promises of much needed aid. Making good on

those promises with efficiency will be imperative to the success of containment

efforts. This past week, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon set up the UN Mission

on Ebola Emergency Response, and the UN opened up a regional headquarter in

Accra, Ghana to assist regional efforts in affected countries.

Global health

experts estimate that in order to make real progress on stemming the tide of

Ebola in the next two months, at least 70% of those infected should be

receiving treatment and 70% of burials should follow safety protocols. This

ambitious goal will require significant assistance from the international

community in terms of money, infrastructure and health personnel. The 800

additional beds promised by the international community fall woefully short of

the 3,000 beds estimated by the WHO as needed to meet current demands. Cuba has

sent 461 doctors and nurses, China has sent a 59-person team and a mobile lab

to Sierra Leone, and Britain has promised facilities for 700 new beds.

Economic Impact

The Ebola

epidemic certainly poses a genuine threat to international public health and

security, which has galvanized the international community into acting, but the

epidemic has already devastated the economies of the hardest hit countries.

Though Guinea has been able to stabilize Ebola infection rates, the country is

facing significant economic losses. $30 billion worth of infrastructure and

mining construction have come to a halt, and the country faces a loss of up to

2.5 percentage points of estimated GDP growth. Multiple industries have been

impacted in Liberia by decreased worker mobility due to internal travel and

public transport restrictions: fuel sales have dropped 20 to 35%, and rubber

and palm oil production and distribution have been disrupted. Misconceptions

about Ebola transmission has fueled beliefs that the disease can spread through

crops, water or food, leading to communities abandoning agricultural

production, which is only compounding existing food shortages from

transportation disruptions.

What’s Next?

The reach and

intensity of this Ebola epidemic remains to be seen, but efforts to contain and

quash the disease are likely to ramp up as the CDC confirmed yesterday the

first ever case of Ebola diagnosed on US soil. The patient, a man who traveled

from Liberia to Dallas, is in serious condition and is being treated in

isolation at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital. Some people who came into

contact with the man after he became symptomatic, including school-age

children, are being monitored for symptoms as well, while a CDC team has been

dispatched to Dallas to investigate and monitor for 21 days any other persons who

might have come into contact with the patient.

The hysteria has

already begun to spread in light of the Texas diagnosis, with Americans

unnecessarily panicking that there will be an Ebola epidemic in the US.

Hopefully, this incident will increase pressure on the pharmaceutical companies

currently testing and producing the Ebola vaccine. The CDC has increased

ongoing efforts to raise awareness about affected countries, important travel

precautions, and the symptoms and transmission of the disease. Ebola doesn’t

spread until a person is symptomatic, therefore proper steps should be taken to

investigate travel histories of all those entering the US in order to monitor

those who have traveled to West Africa. If medical teams are able to isolate

and treat those who show the slightest symptoms, as well as any persons who

have had recent contact with the infected person, there shouldn’t be an Ebola

epidemic in the US.

As for West

Africa, let’s hope the international community musters up the resources and efficiency

needed to contain the disease before too many more people die.

No comments:

Post a Comment